| rosanista.com | ||

| Simplified Scientific Christianity |

Why do people pray to saints? Many people do, and many have done so through the ages. The petitioners come from different religious persuasions. Sometimes the petitions are successful. With these successes, one wonders if saints are special agents. Wouldn’t it be more effective and efficient to go directly to the Source?

To answer these questions, it is necessary to understand, at least a little, what prayer is. Prayer is thinking, concrete thinking; a special kind of concrete thinking. In the Rosicrucian philosophy we learn that concrete thinking is an evacuative activity. In concrete thinking a thought form is produced in thought stuff. In effect, a thought form is hollowed out of thought stuff. The Thinker, the Self, does the hollowing or evacuating.

Here in the chemical subdivision of the physical world, we like to say nature abhors a vacuum. It is difficult to create a complete physical vacuum. In a physics lab a vacuum is created in a sealed, bell jar using a vacuum pump. The vacuum pump doesn’t pump vacuum, it pumps air out of the jar leaving it empty of chemical stuff. It doesn’t pump the ethers out because ether is too rare, light still passes through the jar. When the seal is broken, one can hear the air rushing in. A similar sound can be heard when opening vacuum-packed food.

The laws of nature in the world of thought are different from the laws of nature in the physical world. However, the principle of analogy, the Hermetic Axiom, functions throughout all worlds, so there are some analogies between physical and thought evacuation. One doesn’t need an apparatus in the world of thought because one works from within rather than from without. In the physical world, the form for the vacuum is determined from without by the bell jar. In the world of thought, the form is determined from within by the intent and skill of the thinker. There are properties of concrete thinking for which there is no analog in the physical world. For example, thought forms are combinative in marvelous ways amazing to our earthly consciousness. Another thing is that thought forms emit tones, some say they sing. These and other differences are not germane to our topic, but the form is.

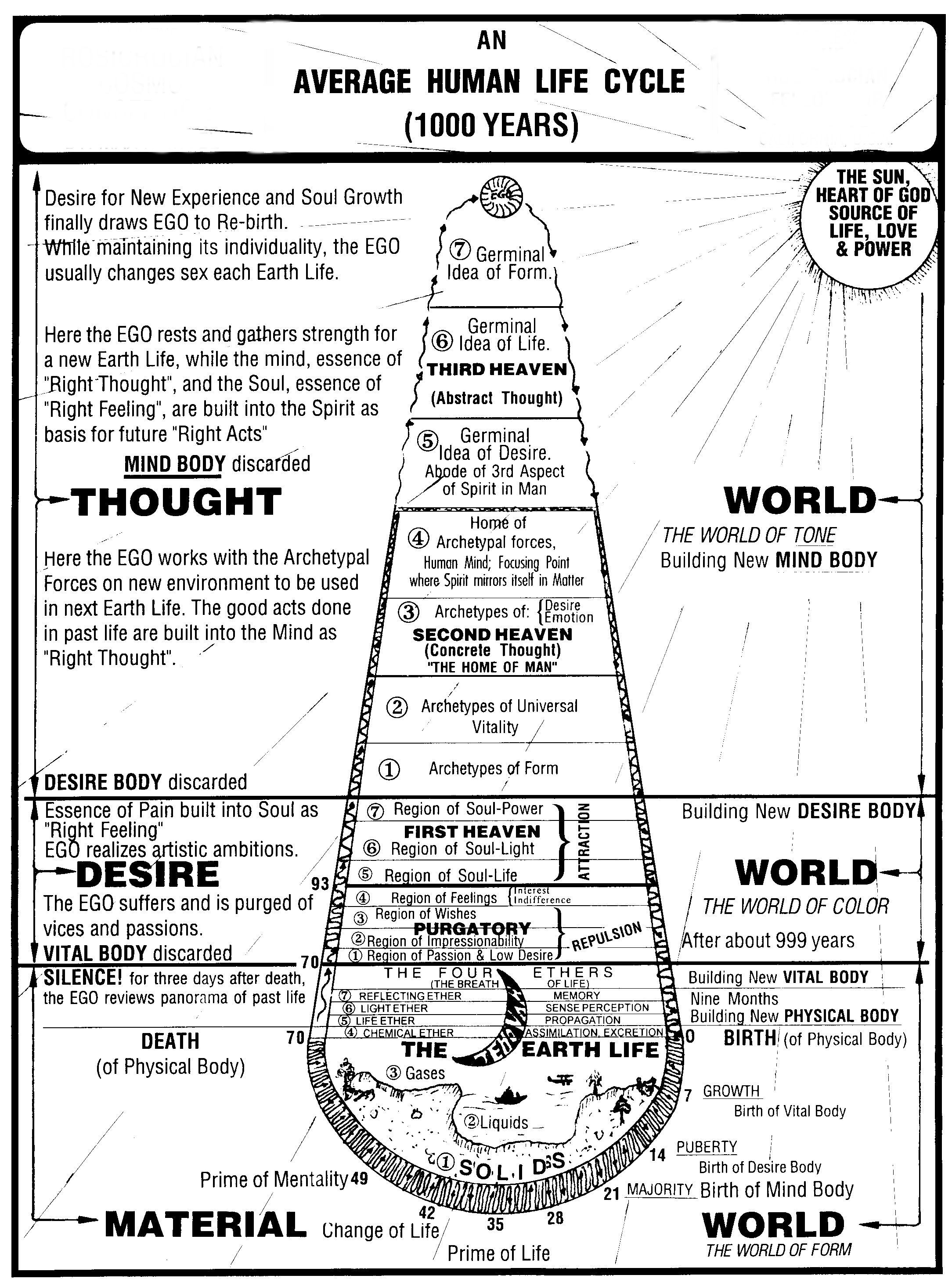

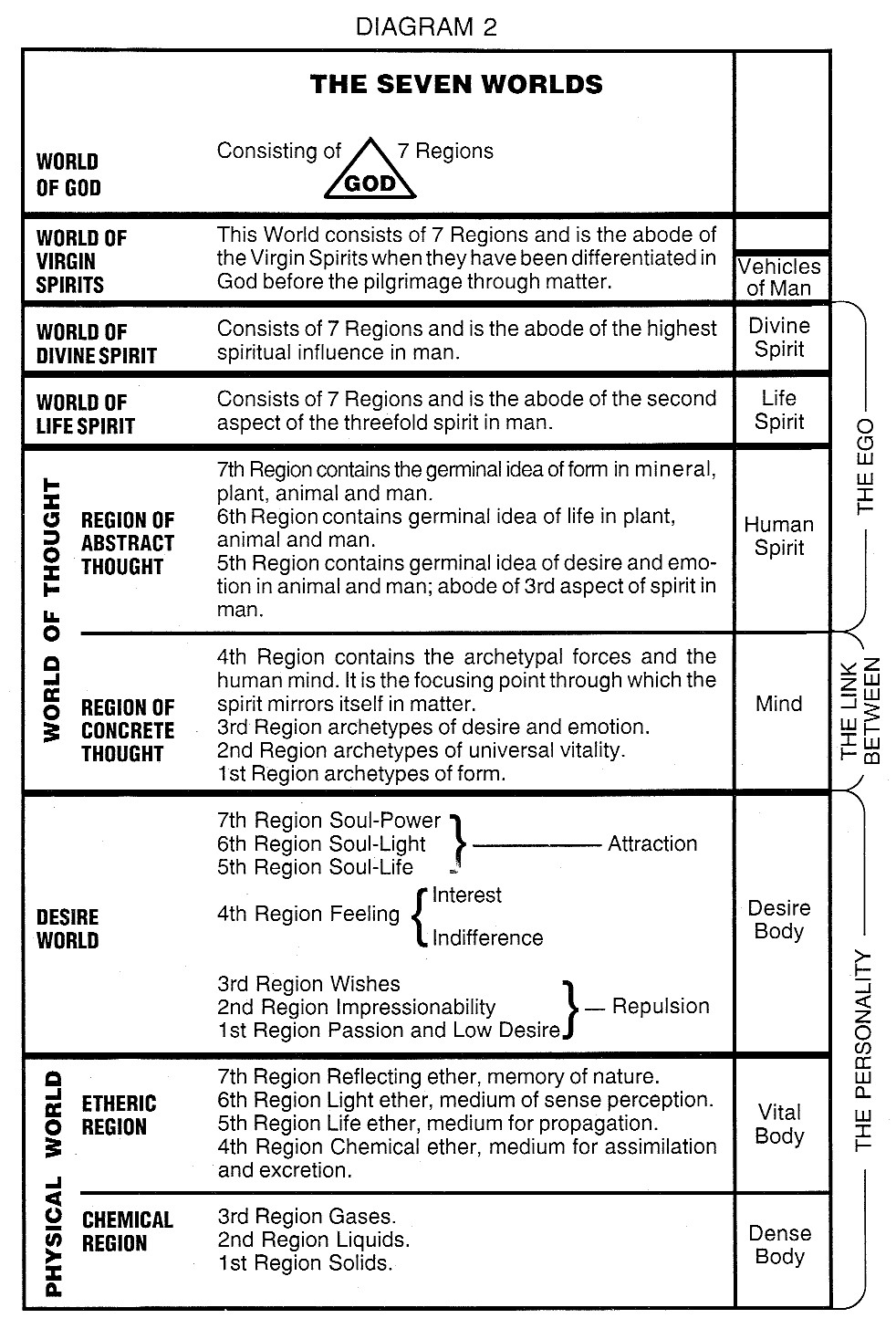

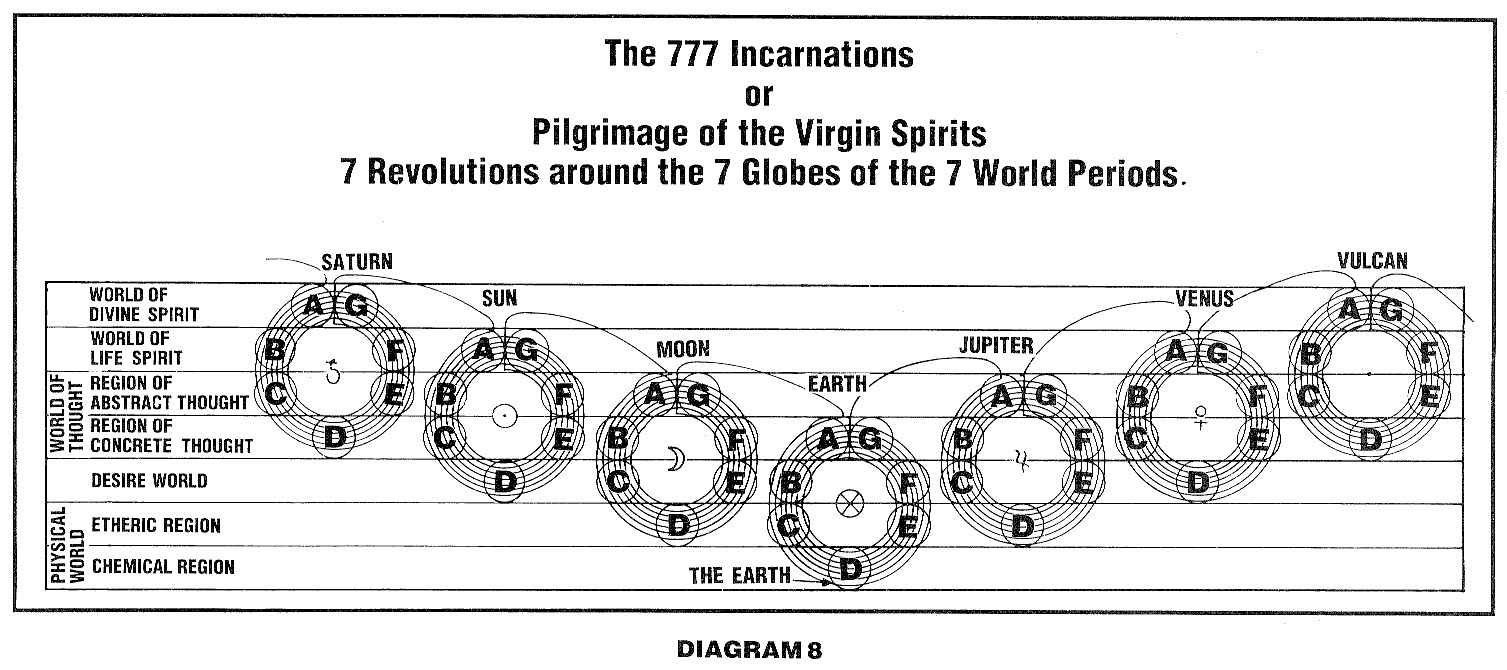

To understand why the form is important, we have to understand the vacuum better. The thought form is an evacuation of thought stuff. It is not an evacuation of the higher states of spirit. In this regard, it is analogous to the physical vacuum in the bell jar, where there is not an evacuation of the ethers. In the same way that the ethers permeate the physical vacuum, Life Spirit permeates the thought vacuum. The life of Life Spirit is what vibrates the thought form. The divine power in Life Spirit is what answers our prayers. This is why prayers in the name of Christ, whose home is Life Spirit, are so effective — “Ask whatsoever ye shall ask in my name, that I will do, that the Father may be glorified in the Son.” Seen another way, Life Spirit is pure truth, out of which truths or principles are conceived, from which principles come all concrete things. “I am the truth.” Thus, Life Spirit is the truth contained in thoughts. Knowing this, is what led Plato to question, through Socrates, whether all thoughts aren’t true. To answer that would lead into macrocosmic thinking versus microcosmic thinking, and other fascinating topics, which would lead us away from our goal. A simple, generic answer is that Life Spirit can be anything, but what it becomes manifest as, is determined by the thought form. What is thought, is what becomes. There are qualities in thought. One quality of thought is the intent of the thinker, i.e., what is being thought out. Another is how well the thought is formed. A poor thinker with good intent, will not be effective because flimsy or leaky thoughts, so to speak, will be created. Not all prayers are effective prayers. Bearing these things in mind we need to understand thinking more clearly.

In third heaven, the abstract subdivision of the world of thought, the threefold spirit or Self, is an ideator, combining or creating ideas. From this perspective, transforming ideas into concrete thoughts is a matter of projection. Ideas are combined and projected through the lens of mind into concretion. However, that is not how most human thinking is done at this time in the evolutionary creation. At present, the Self has drawn into the concrete mind and does its thinking from there. It is the Self in the concrete mind that is the Thinker, the evacuator of concrete thought forms. Concrete thinking is not a sterile, mechanical process, though some legalistic minds would like to make it out as cut and dried. Concrete thinking is creative. It is not like a machine, or electronic device, producing tonal pitches. It is more like the human voice intoning with myriad inflections. There is one general attitude to concrete thinking that is responsible for the evacuation. The general attitude is an attitude of questioning. One might even say all concrete thinking is questioning. In questioning the thinker sucks out thought stuff, so to speak, to produce a thought form to hold the truth. This is true of all forms of concrete thought activity. An artist sketching or drawing is silently asking, “is this the right line?”; a scientist is asking, “is this the solution to the problem?”; a parent is asking how to educate a child. All are questioning, all are creating thought forms to contain insight.

As said earlier, prayer is a special kind of thinking, and it is special in several ways. One way is intensity. An effective prayer is urgent, the prayer is asking with great intensity. The whole being is put into the prayer; thoughts, feelings, everything. Wanting someone suffering to be healed is urgent. Another way that prayer is special, is focus. Effective prayers are focused on specific ends. One doesn’t successfully pray, “let there be healing in general.” One prays specifically to succeed. The focus of prayer, whether it is asking for something, or whether one is asking for worshipful connection, is focused on the heart or center of divinity. Whereas a detective working on the solution of a mystery, or a painter selecting the perfect hue is not focused on the Universal Spirit. Prayer is also special, in that the person praying believes the prayer can and will be answered. Some non-believers have become believers by praying in desperation and having their prayers answered. This is important, because one is not handicapping one’s self with doubt, which is one of the limitations of skeptical thinking. “And all things whatsoever ye shall ask in prayer, believing, ye shall receive.” Believing is found in other kinds of thinking, but it is not always as integral and essential as it is in prayer.

The examples of praying given above are specific, and they usually involve something urgent. Some people only pray in emergencies or crises, and at no other time. Such prayers can be effective if the “special” contingencies are met. However, prayers are more likely to succeed if the person praying is skilled through practice. This means establishing and building a prayer life.

Max Heindel strongly recommended developing a prayer and devotion life, and he gave tips for doing so. Spiritual aspiration is the profession of our lives, so a devotional life must be part of it. In developing a prayer life, the watchwords are like the old hymn, “Nearer my God to Thee.” Developing a prayer life isn’t easy. In the Rosicrucian philosophy we are admonished to live lives of work and prayer. As far as this writer can tell, prayer is work, very hard work, very slow work. Even getting started is difficult.

All spiritual exercises are heuristic, self-educational. Spiritual exercises are the highest form of learning by doing. It is important to keep in mind that, when turning inward, everything is important, and everything is educational. Everything serves the end of spiritual exercises. If one turns inward in prayer and finds the traffic outside annoying, the irritation is meaningful. It is likely a sign of success. One’s consciousness has been raised enough to be more aware of the environment. Then one may exercise one’s divine freedom in an act of choice. One is free to choose to focus on the traffic noise or on the Object of prayer. Freedom. Freedom from the onset.

Not all of the distraction in prayer comes from the external environment, most of it arises from within. Psychologists call it resistance. Spiritual aspirants find that it comes from the lower nature, the pseudo-self in the desire body. The consciousness of this false ego is limited, compared to the true Self, but it is still formidable nonetheless. In its cunning, it knows that its liberty to direct the personality willy-nilly to its own ends, will be over if it is tamed and directed by the true Self. It does not want a prayer life to be established. If one tries to establish a daily prayer session without fail, it is remarkable how many excuses arise to distract one. One may feel tired, or other things might seem more important, or any number of things are thrown up as plausible excuses. One must assert one’s will to be free in one’s own being.

One of the objectives of developing a prayer life is self-intimacy. In some respects, self-intimacy is not much different from intimacy with another. There are definite similarities. One of them is that it takes time to develop intimacy. A prayer life is not developed overnight; it may take years of self-application to become inwardly intimate. Consistency is another similarity. One does not form intimate friendships by infrequent interactions, and only when it is pleasant and convenient, one must share with a prospective friend regularly, through “thick and thin,” as the idiom says. The great pianist, Pederewski, once said: “If I miss one day of practice, I notice it. If I miss two days of practice, the critics notice it. If I miss three days of practice, the audience notices it.” It is like that with prayer. The spiritual will to pray is as gentle as it is firm. Harsh discipline is not likely to reach the subtle spiritual worlds. Some mystics have likened a prayer life to courting a loved one that one never wants to miss or be without.

Developing self-intimacy can be like the early stages of a marriage. During courtship everything is sweetness and love. However, when one marries and must be with someone every day and in all circumstances, not everything is pleasant. Neither is everything pleasant in a prayer life, especially in the early stages. As with the traffic noise, success is not what one expected it to be. We must remember that all thought forms live, so all prayers are answered in the life of the prayer, which often exceeds our personal life. Even the feeble prayer of a tyro brings light into the inner being, if one is sensitive enough to see it. When our inner being is illumined, things stand out in the light of spiritual consciousness. Some of these things are not pretty. Some of them are glaringly intolerable and must be either transformed or eradicated by retrospection or some other spiritual means, because one can no longer live with what one sees in one’s self. Developing a prayer life is character building, and spiritual becoming. One would expect no less in addressing divinity.

It isn’t all bad. Most of it is good, almost unbelievably good. Sometimes too good. This writer knows of cases of people addicted to the joys of prayer such that they neglect worldly responsibilities. That is clearly fanaticism, which will eventually have its consequences. A progressive, sustained prayer life is not fanatical. When true to the conscience, it builds the most positive aspects of character. But character building is slow, even with excellent tools like retrospection and prayer. It might take several rebirths before this writer feels comfortable with his progress in a prayer life. People who have been successful in developing a prayer life report there are a progression of stages in prayer. Perhaps none has done so better than St. Teresa of Ávila. Surprisingly, though her horoscope is predominated by significators in fire signs, especially, and air signs, she writes about stages of prayer in four stages of water. Her description of stages of prayer is magnificently written with the direct simplicity of one who makes appeals to Divinity without frills or complications that would distract. One learns to anticipate a never-ending succession of stages, each better than its precedents.

Appeals to divinity sometimes present a problem to newcomers to a prayer life, especially for questioning Rosicrucian aspirants. During the past fifty-some years in which this writer has been working on a prayer life and trying to help others do the same, one question has arisen much more often than any other. To whom does one pray? Rosicrucian students are taught that their innermost being, the Self, is a divine being. It is our center. The same focus in the macrocosmic scope of our solar, creative manifestation is called God. Max Heindel tells us that the being we call God is the Source and goal or end of everything in our creation. Then, there is the Supreme Being on the first or highest cosmic plane, the ultimate creative being. Finally, there is the Absolute, sometimes referred to as the One by Max Heindel. The Absolute is also sometimes referred to as the Unspeakable, i.e., everything that is, and is not — being and nonbeing, and even something that could be neither being nor non-being. It is even beyond conception as a being. To whom does one address one’s prayers? The answer is that it might not matter. The Bible tells us that to know God (Divinity), one must believe God is. The Bible also tells us God is a spirit and must be worshipped in spirit and in truth. One does not address spirit, or a spirit, as one addresses a person. Meister Eckhart said, “Some people want to see God with their eyes as they see a cow ….” The central quality and character of spiritual being is central to itself at whatever level. The centering is what counts. If one is focusing on whatever level, one is not centering. If one is addressing a friend, one focuses on the friend or the communication will not go well. The friend, in person, has a specific location, spirit does not. The center of spirit is everywhere. “The ways of God are strange to the ways of men.” It is the centering intent of prayer that matters. To the degree that one addresses the Center, is one in prayer. This, too, is one of those open-ended things about prayer, one continuously improves at centering and penetrating more deeply. The same idea applies to distance as well as direction. If one considers the object of prayer as distant, it will be distant. One focuses on the heart of God irrespective of distance or direction. “Nearer my God to Thee,” is more than a religious sentiment.

There are many more important things about prayer which are not germane to answering our initial question. This much does provide an answer to, “Why do people pray to saints?” There is an open-ended scale of prayers. It stretches from those who pray to totems to those praying in spirit to whatever degree of centering on divinity. Those who pray to saints are on the more concrete end of that scale. They need a concrete object on which to center. Hopefully, the saints will lead them to praying more toward the Center of Being. Our actions in prayers, as examples, might also help.

|

|

|

|

|

Contemporary Mystic Christianity |

|

|

This web page has been edited and/or excerpted from reference material, has been modified from its original version, and is in conformance with the web host's Members Terms & Conditions. This website is offered to the public by students of The Rosicrucian Teachings, and has no official affiliation with any organization. | Mobile Version | |

|